If, on a winter’s night

(Maybe next time I could try talking about the interweaving of the wanderer and the Doppelgänger??)

Photo courtesy by Barbican Center

Once upon a time, Arthur urged me to expand repertoire other than Schubert. Indeed, I have self-indulged quite a lot with Schubert—I simply couldn’t live without Schubert. I could probably endure without Wagner. Schubert is essential for my mental wellbeing and intellectual acuteness. Think about the word painting in his Lied cycles. Think about the eternal loneliness of his nameless wanderer. Think about Wien and his non-influential short life in Wien. Earlier this summer, I took advantage of the Steinway in UC Boulder and learned D. 958, while I spent the days attending philosophy seminars. Since then the c-minor epic is reminiscent of the smell, the look, and the temperature of Colorado mountains.

I simply love the intimateness of Schubert. I briefly addressed his unabashed frankness for fragility and his forward-mindedness on notions of masculinity (aka. gayness). Recently, I unraveled another Schubertian spectrum by virtue of Hans Zender’s transcription of Winterreise. The Schubertian wanderer more or less turns out to be Kafkaesque. Why?

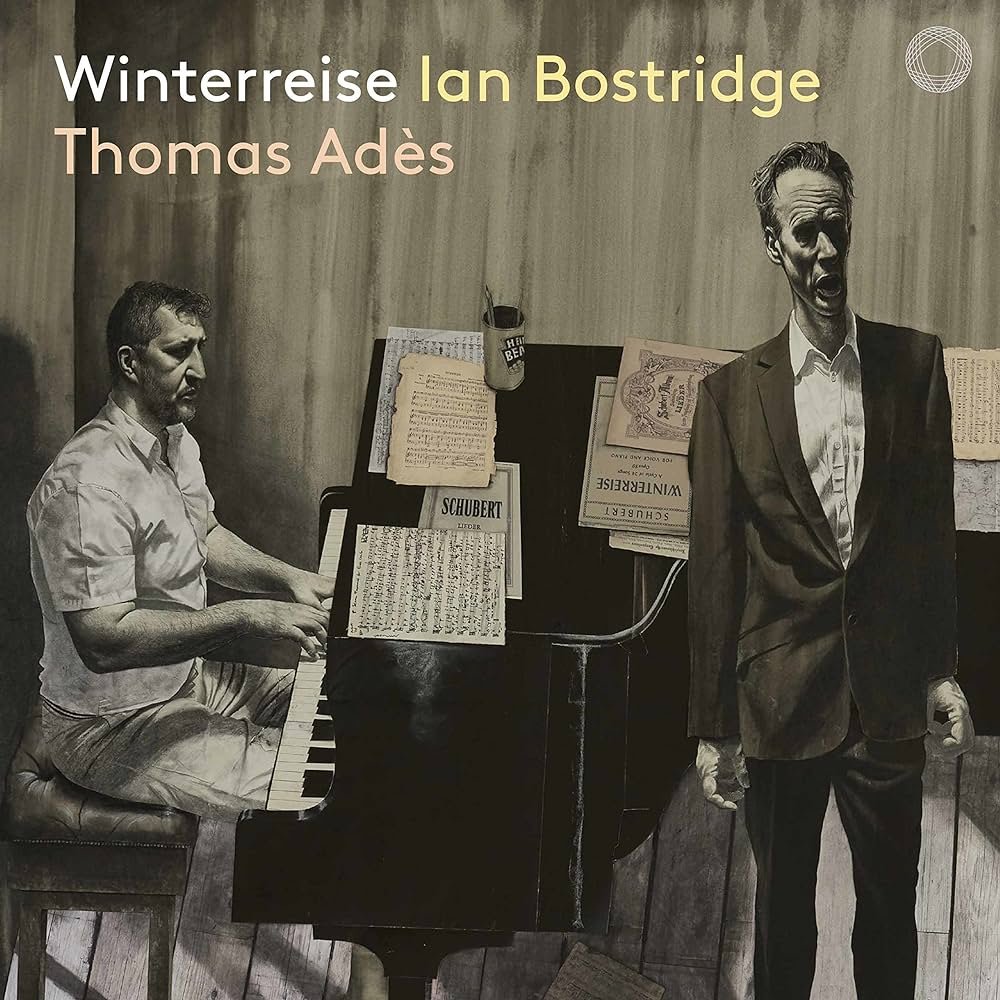

Ian Bostridge is the best ever tenor for the Winterreise. His unparalleled impersonation of the wanderer gives me tearful goosebumps.

I could safely say Schubert is much invested in solitude as a central theme of human existence. The wanderer has a high frequency of appearances throughout Schubert’s compositions: Das Wanderer (the Lied in Die schöne Müllerin, the Wanderer fantasy (the piano sonata), and Winterreise. I expect myself to return to those works again and again in the rest of my life, lest I am no longer a wanderer, which I know I will certainly be.

On the other hand, Kafka pursues absurdity. K., a trivial character got caught in the machinery of systematic oppression, always finds his life pointless. He couldn’t reach the castle, despite countless attempts and detours. He couldn’t persuade his families to sympathize with his agonies, despite his metamorphosis to an insect. He is indicted in a trial without being revealed the sentence of his crime. He locks himself up in a cage and starves himself to death as a maniac artist.

K. is apparently and undebatably unhappy. K. synchronizes perfectly with current figures who are likewise caught up by the insidious never-ending competitiveness. Yes, I am talking about my generation. Compared to the Schubertian wanderer, K. fits better to our problems.

Currentzis conducts the Winterreise.

Hans Zender shows the synergy of Schubert and Kafka. Schubert’s works are highly translatable to alternative instrumentations. Liszt is one of Schubert’s avid transcribers. I have to admit that I first got to know the Wanderer fantasy through Liszt’s orchestration (performed by Boris Berezovsky), not through the original piano version. Hans Zender picks up, reinvents, and synergize the Kafkaesqueness with the Schubertian wanderer.

First, the transcription consists of quite a lot of repetitions that are previously non-existent in the song cycle. Repetitiveness? Does it sound familiar to a Kafka lover? Be a workaholic for one more second, we will all degenerate to cockroaches. Hans Zender duplicates the instrumental length. The opening is expanded to ten times longer. I almost felt suffocated during the first time I heard the opening, until the original harmony arrived.

Second, the instrumentation consists of a windmaschine, chimes, drums, a xylophone, an accordion, a guitar, and the usual woodwinds and strings. The tenor also equips himself with a speaker from time to time, especially when he needs to express certain existential angst. After a brief research, I found the following explanation:

My lecture of the Winterreise does not demand a new expressive interpretation, but instead systematically exercises the freedom which all interpreters allow themselves intuitively, such as: instrumental dilation i. e. acceleration of the pace, transposition into other keys and elaboration of characteristic color timbres. In addition, there are further ways of "reading"; the music jumping around in the text, repeating certain lines, interrupting the continuity, comparing different expressions of the same phrase... All these new possibilities are subjected to my compositional discipline and form autonomous formal processes which are imposed on Schubert’s original. The transformation of the piano tones into a multifaceted orchestra full of resonance is only one of many aspects.

— Hans Zender

Maybe Hans Zender doesn’t have Kafka in his mind at all during the transcription process. Maybe it is our mind whispering and signaling a Kafkaesque impression that projects our current mode of wanderering.

I have been fetishizing this book since I encountered it in Boston MFA in 2018. This book is also probably the only book (among a few others) that I haven’t regretted buying yet (I regret most of the stuff, not just books, that I have spent money on).